It is not easy to see the sky in Beijing. Sometimes because of the storms, sometimes because of the fog and most of the times because of the tangible pollution surrounding the city the atmosphere becomes a ghostly mass in which the buildings are merely glimpsed. At night the stars cannot be seen, only flashing sparkles draw your attention in the heights anywhere in the city. In fact, they are the construction workers welding steel climbed on to the structure of new towers spreading in all directions. The metropolis is transformed by day and night, it changes, it renews itself and expands unstoppable as a living organism would do.

The same scenario is repeated in most of the Chinese cities. Their urban development is obvious, and their growth can be perceived in days, even hours. These formal and noticeably transformations are the result of a deeper change, the one experienced by the Chinese society. The social factor is essential to understand a country that is building itself up. A society driving a change –obviously controlled from above in a long search for modernity- but with a contagious energy nurturing the admiration and prejudice of the exhausted Western economies that are fixing their eyes on it.

The most populated country in the world has seen how an emergent social middle-class arises, aiming to get better labour opportunities with a prominent urban and consumer character. All this added to the particular demographic situation caused by the one-child policy. At the same time and as a result of the new opportunities coming up in the different industries of the country, a new high-class keen for exclusivity and luxury goods proliferates.

Urban development is always regarded as an evidence of economic activity. Europe is suffering nowadays the consequences of a crisis influenced by the real estate bubble. The construction boom, that transformed the cities of the Old Continent, has left a surplus of housing in several countries, as well as abandoned construction sites and cancelled projects. While Europe is facing the task of reinventing its development model, China is experiencing optimistic times in which architecture must answer some questions related to new interpretations of the domestic space, different relationships between people and expectations of a promising future meaning a change of life. Most of the Chinese society is demanding innovation, a break in obsolete city models and a sort of identity-based on differentiation.

Social changes and demographic growth have put Chinese cities in a situation of development and needs of expansion exceeding the capacity of the emerging urban planning. The new cityscape usually brings to our mind the clean state radical projects considered in Europe at the turn of the 20th century. The postulate of Le Corbusier, in favor of breaking with the architecture of the past to build one for the future, and his controversial proposal for the demolition of the urban centres, occupying the vacant space with huge skyscrapers arranged in a military order, seems to be the principles on which the Chinese society has based its future.

Nevertheless, if the formal result of this process can evoke the avant-garde ideas of the modern movement urban planning principles, the Chinese situation has no much to do with its content. As it happens in other countries under development, the reproduction and implementation or foreign models, not only from the architectural point of view but also at a technological and sociocultural level, is a key point of the quick development of China. In consequence, when the urban sprawl exceeds its own natural capacity to be thought and planned, the only way to satisfy the demand is to adopt existing models and create a repetitive standard.

Likewise, the gradual city migration policies as well as the development control of the different areas of the country for the balance of their economies, complete a very special and contrasted modernization scenario characterised by the management of the land –property of the government-, and its singular method of control about profit and use.

From North to South vast residential areas built under the same model and typology can be found: long and narrow blocks with two apartments for each staircase facing South with green areas in between. Their façades are normally decorated with European architectural styles, and the real estate market usually launches marketing campaigns focusing not in the characteristics of the building but in offering new values related to distinction, luxury and the high social position meaning a way of living based on foreign models.

These high residential complexes, commonly isolated from the urban fabric, and highly dependent on private transportation systems as the only way to access them, become small ghettos of Western taste. In fact, simulating paradoxically an idea of modernity totally built up in China.

The extensive use of a single model of development becomes evident when the conditions of the territory are adverse. In the past year, AQSO has worked together with LKS engineers on the development of a strategic urban planning for the city of Pengshui, located in Southwest China, part of the Chongqing municipality. This intervention of an area of more than 3,000 hectares covers the city centre located at the confluence of the Yangtze River and Wuijiang River and other four districts in a rugged mountainous area. Most of the recent transformations of the city have turned into problems due to a wrong land use system: suitable for plain areas, -mostly residential towers have been built-, but incompatible with the topographical conditions of the place. The city needs a model of development adapted to the territory that the current real estate market has not been able to discover and provide. If originally the downtown was able to adapt to the land, the rapid current growth has been obliged to satisfy the housing demand using a conventional residential high-density standard model.

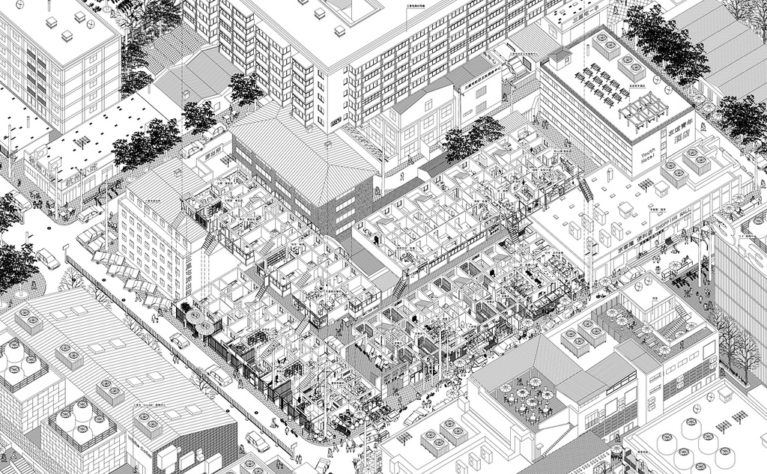

In contrast to this abundantly extended formula operated by a real estate boom becoming more and more latent, the old city coexists keeping a complete opposite model. Traditional neighbourhoods, like the Beijing hútòng, are conceived as low-density areas where diversity, social interaction and urban mobility are curiously closer to the compact and sustainable urban development model adopted by Europe since the post-modernity.

The current architectural Chinese scenario is therefore made up by a varied group of contrasts. After a search for modernity more or less reconciled with the tradition of the past, the result is a multicultural patchwork where factors associated with repetition create heterogeneous urban spaces at a certain scale, but homogeneous as a whole. This means a vast scenario made up by similar cities, sometimes even totally identical, a result of the same process. However, in its urban fabrics, you can find impossible disparities, incongruous mixes and a repeated diversity understood as a unique personality but never as a differentiating one.

Identity in a city is not only about the construction of strategic buildings with iconographic character, which can evidently qualify the place and act as catalysts of a change. It is more about an urban planning linked to the territory and focused on the search of specific development models for every single particular location. The research program Hutopolis, involving European students for the investigation of new urban development formulas based on the principles of the traditional hútòng, aims to discover urban, social and architectural solutions to provide alternatives to the city model gap currently happening in China.

Urban development is all in all not just a quantifiable process in terms of production, the extension of the city or speed in land occupancy, but as a process itself, it is defined by time, by changes and transformations of the space up to fulfil the needs of its inhabitants. This process is therefore as generative as regenerative and as constructive as destructive at the same time. The transformation taking place in China has started from a spectacular growth able to satisfy the needs for the most immediate future, but it will be consolidated after subsequent changes and adaptations. Under a clear atmosphere, the city will show its evolution to keep mutating. Architecture has the challenge to face evolutions that will trigger a new identity, will produce new typologies and will consolidate a sensitive creativity linked to history, future and past.